by Choghakate Kazarian

I met Emanuele Becheri about ten years ago, in his studio in Tuscany. He was then known for works that I would qualify as gestural conceptualism: drawings made “blindly” by folding paper in total obscurity or letting snails run on paper. I was also very interested in his videos that captured with high intensity the small, yet dramatic sounds of fire, wind, or an upcoming storm.

When in 2016 Becheri turned to sculpture, a new territory for him, I was bewildered. Happy that he had turned aside from a path that, despite its many achievements, would have led him to a dead end, I was still uncertain about these new experiments. Actually, he did not make his way to sculpture directly. He first told me about his musical practice, to which he was seriously committing. Although I did not fully understand the excitement in these instrumental improvisations (he called them “schizzi al pianoforte”), I knew that it could be a liberating process, something that might lead him toward a more direct and primeval approach to art. Becheri started making figurative and highly expressionistic drawings. Although I liked their free spirit, I must admit that some of them were scary, as if the works of a mad man or the depiction of madness, to say the least. I could only think of Goya or some Gothic fantasies.

I was seeing them only through reproduction and could not determine the scale. Although I imagined some to be large, most of them looked tiny—the results of an obsessive mind, nightmarish visions transcribed during hellish hours of the night. I was almost worried for him. But at the same time, I knew this to be necessary. He could not go back. And from these drawings to the sculptures, it was only a short step.

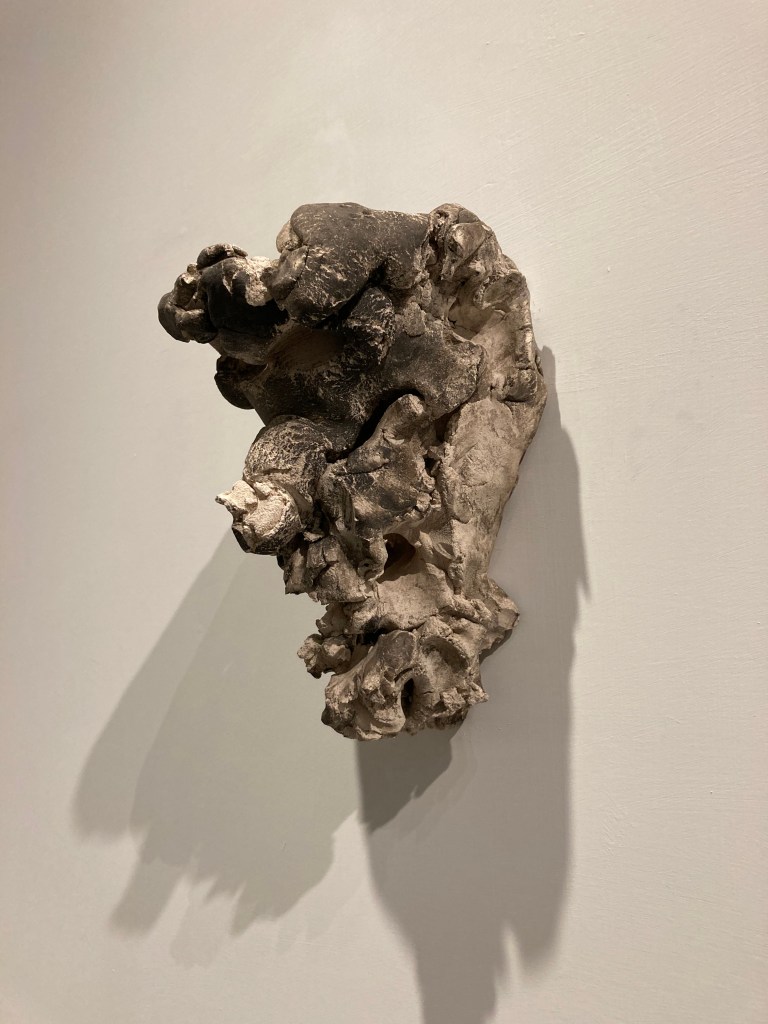

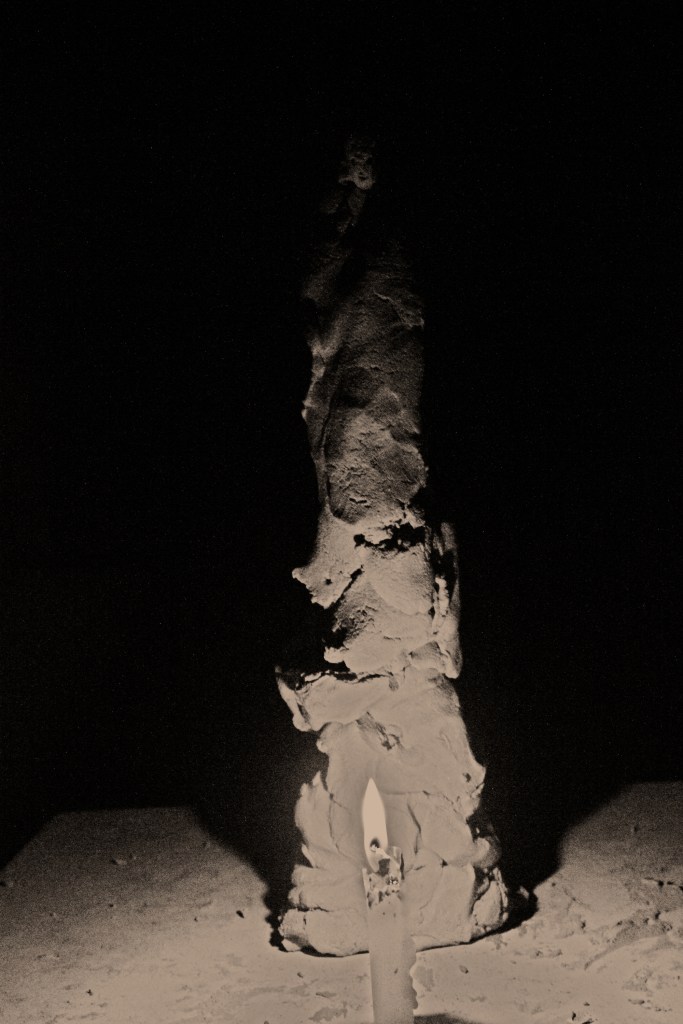

In July 2016, Becheri sent me pictures of his first experiments in sculpture. They had the dark spirit of his drawings but contained a new dimension, a tactile pleasure. They were made of wax, plasticine, and clay (which would become his favorite medium). I knew of his interest in the dramatic sculptures of Bernini, the gestural fantasies of Lucio Fontana’s ceramics, and the fleeting shapes of Medardo Rosso’s waxes. I wondered what this confrontation with the masters would bring. But also present was Becheri’s own romantic mood, with his taste for monochrome, patinated surfaces, and a nocturnal darkness, something that was accentuated in his black-and-white photographs of the works. (Long have I been wondering if the artworks were actually the photographs themselves, where the sculptures appeared in a pictorial veil.)

Although I was still not sure about all this, I was longing for its outcome. I was somehow hoping that Becheri would undergo the same changes I had myself. (I went from the more or less conceptual taste of my youth—I was fascinated by Marcel Duchamp’s 50cc air de Paris and Piero Manzoni’s Merda d’artista—to the more expressionistic side of art.) The fact that I followed his intense period of creativity from afar, through emails and photographs, did not make things easier. I needed to see the work. And the sensorial deprivation of a covid-19 world made the urgency of a three-dimensional experience even more pregnant. So I went to Italy.

The Museo Novecento in Florence had opened a show dedicated to these sculptures in January 2020. A retrospective of the last four years of work, the exhibition made me realize how serious all this was. Far from being a transition, it was an entirely new body of work—probably Becheri’s most intense output. In four years he had produced more works than in his entire career. The sculptures were as I imagined them but different. What in the photographs appeared as shadows or dirt from the studio was actually manganese oxide. Becheri had applied it either evenly to the surface or had randomly scattered it while handling the fresh clay. This dark powder was the only coloring and surface decoration that he would allow besides the chromatic variety of the clays (although rarely red). Seeing them in person, without the intermediating sfumato of the reproductions, the sculptures displayed their grainy skin, emanating an earthy presence.

I needed to see more. So we went to Becheri’s studio in Vaiano (near his birthplace, Prato). There were hundreds of them everywhere. All shapes and sizes. Some were properly arranged on racks, while others were scattered on tables. Some of them, of ambiguous status (in progress or grounded), were waiting on tables or in corners of the studio. All products of consuming years of creation. The contact with clay brought Becheri to experiment with bodily expansions made of terracotta that can be worn or displayed on hands, wrapping wrists or fingers. However attractively welcoming, the surface of the unglazed terracotta was dry and coarse.

It is probably a mere reconstruction from a retrospective perspective, and yet I cannot help but see these sculptures as a natural outcome of his previous work (from blindly folding paper to modeling with hands). What once seemed displaced and unhinged now appears logical and fully legitimate; as if the cooking and baking of clay needed some time to become edible. I realize that Becheri’s work has never been about concepts but about touch. He went from indirect contact to direct bodily interaction. I left the studio with a piece in my hand, holding it tight for hours, experiencing that connection.